Internet censorship in Korea, and the eventual end

2026-01-11

This blog post is written in response to the pearl-clutching prudes and puritans that dictate how I as an adult get to browse the goddamn Internet.

Even though our country is not an authoritarian state and doesn’t have the Great Firewall of China, it’s still widely known for censoring the Internet, something that rudely startle foreigners when they want to go on NSFW sites in their hotel rooms.

Now, if we get into the entire should they, shouldn’t they thing then this blog post will be so long you won’t read it. (I mean you probably already clicked away but still, please pretend you’re reading. Yay, thanks for continuing.) But my take is that censorship leads to overreach, which has already been proven by the way I run into roadblocks accessing sites that I as an adult have the legal right to. So no, I don’t agree that this is the right approach and think they should fix that, but in the meantime let me go over how they actually censor the Internet.

How they (used to) censor the Internet in Korea

Traditionally, the major ISPs in Korea used to poison DNS entries like all the other nanny states and countries that decided they could decide what’s best for you. That means you ask for Google.com and if Google was one of the banned no-no websites (according to some review somewhere), essentially, the ISP’s DNS servers would respond with an IP that is not Google’s and redirect you.

Of course, that was largely patched out thanks to encrypted DNS’s proliferation and the fact that HTTPS stops your browser from loading the scary-looking “Warning” page from the Korean government, especially if HSTS is enabled.

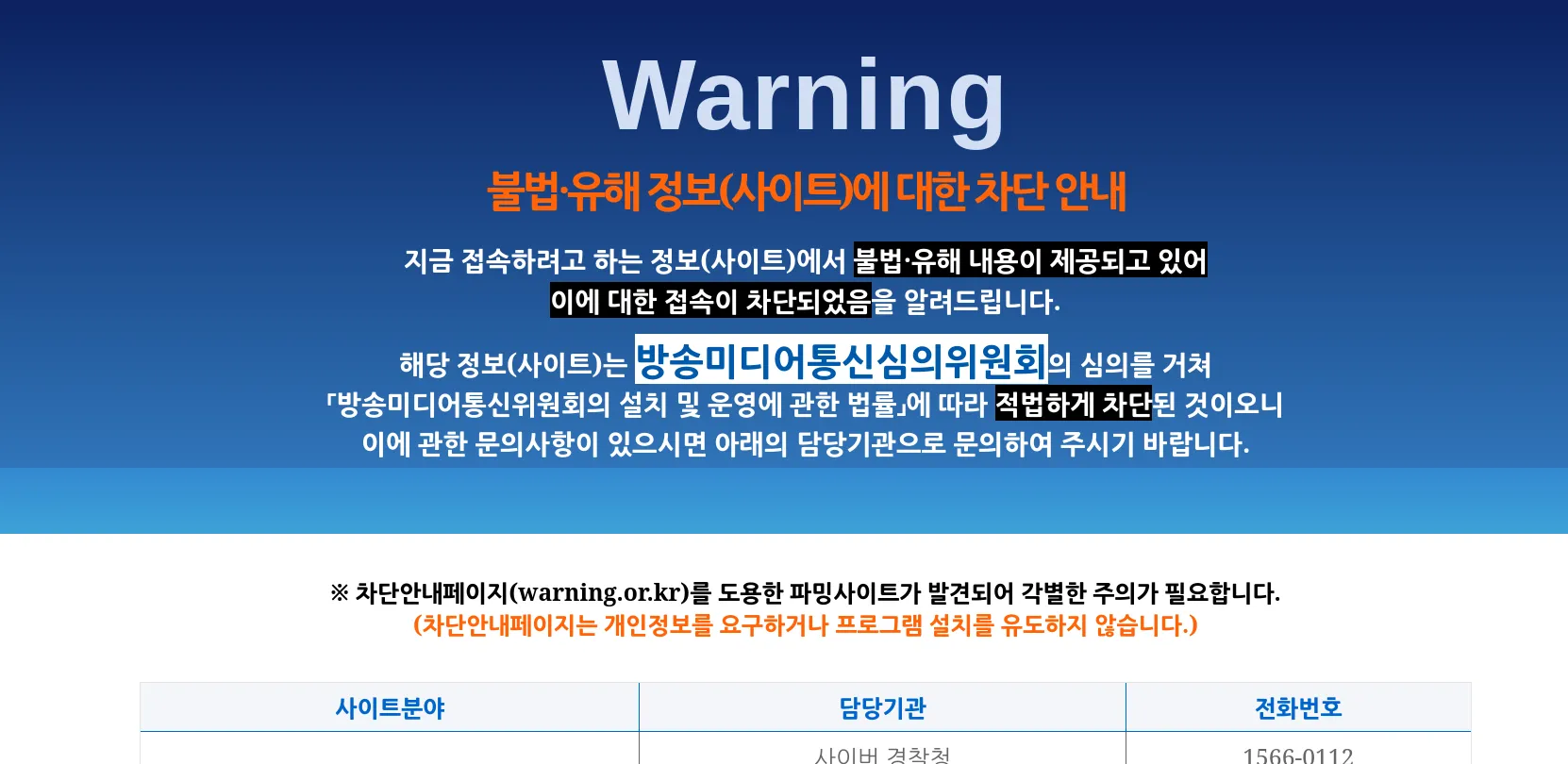

For context, this is what you would see if you got hit by one of those censorship measures:

Ugly as sin, all in Korean (except for the threatening “Warning” text), and some bullshit about how they’re “legally” blocking the site as it has passed through review of some board (read: puritans) that has determined it is either illegal or “harmful” (유해 내용). Except “harmful” in this case extends to totally legal mature content that little Timmy on his iPad shouldn’t be viewing, but since parents don’t know diddly-squat about how parental controls work let us the government do it for you!

As mentioned before, people realized sending DNS requests back and forth on an unencrypted port was a really bad idea, and we quickly patched that with things like DNS-over-TLS and DNS-over-HTTPS. Now, Korean ISPs no longer poison DNS, though it’s still a good idea not to use their DNS servers in case they’re doing anything funny.

So what changed?

How they (currently) censor the Internet in Korea

In present day, ISPs look at the actual HTTPS request.

When you make a request to a server, there is some communication back and forth to establish a TLS connection. One of the extensions to TLS is SNI, or Server Name Indication. Basically, as web servers become more and more reverse proxies and host various domains on one server, it became important to signal which particular domain you as a client were interested in. So the domain name would be specified in the SNI field and the server would send over the TLS certificate corresponding to the domain and everything would continue.

But the SNI field is not encrypted, and thus Korean (and other countries’) ISPs could sniff out which website you were trying to visit, and cut the connection. They can’t really redirect you to the Pennywise website above, but they can interrupt your connection by sending a reset packet.

So how can I get past it?

The easy, boring solution: use a VPN, or a proxy, etc.

But it seems like a waste and a hassle, when all you need to hide is just that single SNI field! Surely there’s a solution to that?

Well, there is. Initially proposed as Encrypted Server Name Indication (ESNI), the latest proposed standard is Encrypted Client Hello (ECH), which now encrypts the unencrypted portions that help set up the TLS connection.

With ECH, ISPs can no longer spy on what is being sent over the wire and to which site you are connecting to.

Great, can I use ECH now?

Kind of.

ECH is supported in most major browsers, but servers must also support it. Support is slowly rolling out, but until it becomes mainstream you may still run into some sites that are being blocked by your friendly Big Brother.

And for clients like curl, the SSL library used must support ECH. As of right

now, the default curl binary as it ships on Arch Linux does not support ECH,

for example.

I ran into this problem with my Rust program, where the connection would succeed

for a given site on my browser, but fail catastrophically on my Rust client. The

dependency that I use, reqwest, recently switched to

rustls, which does have ECH support on the client-side.

There’s no documentation on how I can use it on reqwest, nor

any indication of whether it is enabled by default (so I presume no).

But once ECH becomes mainstream, the only way to censor my Internet access would be to make like China and block all requests that go over ESNI/ECH. And that certainly wouldn’t work at all without breaking a large chunk of the Internet.

I’ll certainly look forward to the day they shut down that ugly stupid warning website.