Why I'm moving away from NixOS

2025-09-20

For nearly one year, I’ve been trying out NixOS, meticulously writing out the configuration for my machines in my repository. Every new program install, every configuration change, for all of my devices running NixOS was carefully packaged up into a commit and put into the repository.

Now, after nearly a year of experimentation, here are the pros and cons that I’ve learned, and why I’m ultimately switching away from NixOS.

Disclaimer

Usual disclaimer because people love to engage in tribalism.

This blog post details why I switched away from NixOS. Some of these pros and cons may not apply to you. Some of them you may find an easy workaround for. Some of them you may find baseless.

Please write about them in the comments in the hopes that it may help others (and if it addresses some of the points in this blog post I may edit it to reference your comment), but please refrain from pushing your viewpoint as the ultimate solution, because it probably isn’t for absolutely everyone. Thanks.

Pros

I just want to get the pros out of the way, because there were certain niceties that I came to enjoy using NixOS!

Fast recovery time from scratch

If my laptop breaks, my SSD dies, or I make a horrible mistake and ruin my workspace, the traditional way of a re-install would dictate I make an install media, wipe my drive, re-install the OS, install any drivers (yes, even for macOS, they don’t ship with literally everything), install all my programs, then set them up one by one.

With NixOS, this is also mostly true, except for the parts after the OS install.

Instead, it is cloning my repository, making a symlink, and running

sudo nixos-rebuild switch. And I get mostly1 my computer back, with all the

programs I installed!

Sure, if the specific programs do not support being configured by NixOS, then I have to set them up, but overall, this drastically reduces the time I have to spend remembering and re-installing all of my programs that I used to have.

Fast recovery time from bad configurations

If I make a mistake configuring something, or if I install a program that I do

not want, recovery is literally a git revert and a sudo nixos-rebuild switch

away.

I can even tell what broke my computer with a git bisect. Imagine bisecting

all the decisions you made configuring your computer to figure out where it

all went wrong. Well, with NixOS, you can!

And because each configuration change can be documented with a Git commit message, you don’t have to scratch your head in six months and wonder why the hell you set things up in a certain way.

Cons

Only two pros and straight into cons? (Yeah, I mean, look at the title of this blog post…)

The friction of installing things

On other operating systems, installing an app is double-clicking an .exe and

going through prompts, or dragging an app to a folder from a .dmg, or typing

sudo pacman -S blender. On NixOS though, every program install requires you to

open up your configuration repository, locate the Nix configuration file

corresponding to the host that you want to configure, and add up a new line for

the program you want to install.

Actually. The full process is going to search.nixos.org, finding the package name of the package you want to install, opening up your configuration repository, locating the Nix configuration file corresponding to the host that you want to configure, and adding up a new line for the program you want to install.

(I know some NixOS experts will say there are commands like nix-locate, but

with my usage of them the past couple of months they aren’t perfect. For example,

finding the dig tool inside the dnsutils package was not something I managed

to achieve with nix-locate but the actual website surfaced it.)

And those are for programs that are tracked by nixpkgs. So what if it isn’t?

NixOS requires you to know or learn Nix

“I’m using NixOS and I didn’t have to learn Nix.”

Maybe, but when you run into this issue, you’ll probably wish you had to.

As long as you stick to the packages available in nixpkgs, you should be mostly

okay with your daily usage of NixOS. But run into a package that isn’t available,

and you’re suddenly in for a world of hurt.

In my case, nimf, the Korean input method editor that I love on Linux, and

python-validity, the software package that powers the fingerprint reader on my

ThinkPad T480, were all unavailable on nixpkgs. They used to be open as

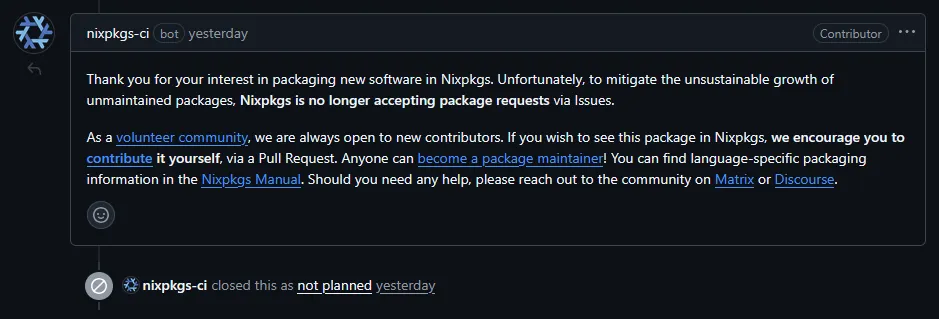

packaging requests on nixpkgs (the latter of which I submitted myself):

but were all closed when NixOS maintainers decided to stop taking any packaging requests2. Now, if you want them, you should contribute them yourself.

If you wish to see this package in Nixpkgs, we encourage you to contribute it yourself, via a Pull Request.

So. If you don’t know Nix, you can’t do those things, because everything in NixOS runs atop Nix, so you better learn it or spend time learning it instead of using the tools that you want to use.

“Isn’t this true for all distributions?” You say. Sure. With Arch, you probably

have to write your own PKGBUILD manifest to package your own program. But that

doesn’t require you to learn a whole new language. (The example I brought up,

PKGBUILD, only means you need to know bash, and

the details are nicely documented in the Arch wiki.)

And suppose you don’t want to learn how to use Arch’s PKGBUILD. Fine. Then

Arch has another escape hatch up its sleeve. You can use PKGBUILDs provided by

the community through the AUR, or Arch User Repository.

“Okay, but the AUR can have malicious PKGBUILDs.” Fine. (We’ll overlook the fact

that you fully trust nixpkgs and all of its contributors.) There’s yet another

escape hatch offered by other distributions. You can just compile and install

the package yourself, no packaging tool config needed. You can’t do that on NixOS,

because the system directories are immutable and you can’t modify them. Any

forced changes will be gone by the next generation build.

I’m not saying that NixOS shouldn’t have been built on top of Nix. That wouldn’t make sense. They literally have it in the distribution name. But through this approach, it makes it tricky for newcomers to quickly adapt and install things that they need if they do not know the core language powering the OS.

“Well, duh, of course you need to learn Nix to work NixOS. It’s like going to

Japan and expecting people to speak English.” Sure, but there are workarounds

to living in Japan without learning Japanese. There are workarounds on other

distributions if you don’t really know their PKGBUILD system and just want a

tool to work. But with NixOS and Nix, immutability comes into play, restricting

a lot of the escape hatches that would’ve alleviated some of those problems.

Some might see it was a bonus, a feature, but I think you’ll agree that it is

at least painful if you do not know these things.

The friction of upgrading things

Say you receive a file that requires version 3.6.12, but the installed version on your computer is 3.6.6. How do you proceed?

On other OSes, you just grab the installer for 3.6.12, install, and be on your

way. Or it’s a sudo pacman -S blender or sudo apt upgrade blender, or whatever.

The point is, you can upgrade just a single package on other operating systems.

On NixOS, from what I can tell, this is not possible. All the package metadata

goes into the nixpkgs repository, and each version bump is tracked

as a Git commit. While this is probably great for the NixOS folks maintaining

everything, this means that all the package versions are stuck at whatever commit

revision is locked inside your Nix “flake” lockfile, until you change that commit

revision to a newer one that includes version 3.6.12.

The trouble is, any commit between your initial commit revision and the new 3.6.12 commit revision also gets included, which includes other package upgrades. Thus, what was a simple single package upgrade now turns into a 20+ min (or even a few hours if you didn’t upgrade for a while!) hassle.

Also, after you’ve finished the upgrading process, there’s no easy way to know

exactly which versions have changed between the last flake lock and the current

one. I only realize that KDE must’ve gotten a new major version bump when I reboot

my laptop and the wallpaper changes, or when I open up a program and get a “What’s

New” popup. NixOS doesn’t really show you a list of packages that will be upgraded.

The speed of compiling things

So why does upgrading take so long?

Usually, when I take a peek at my console while it is upgrading my system, I see a lot of packages being compiled into binary form that can then be installed on my system.

But NixOS has a binary cache, available at cache.nixos.org! Your builds shouldn’t be taking that long! What gives?

Well, as the name of the subdomain implies, packages first have to be built on NixOS’s servers before they are “cached” for distribution. If the requested package has never been requested before, or if there has been a new update to an existing package, a build job has to run before the cached binaries are available for download.

And if there are tweaks to the build process in your configuration, that requires another binary, which is probably not cached by NixOS’s servers. Which means NixOS immediately defaults to compiling the package from source on your system.

You can set up build cache servers yourself, and this means that you don’t have

to turn your weak laptop into a furnace every time you run a switch3, but it’s

yet another thing that you have to configure and keep track of.

Configuring “everything” through NixOS

The beauty of documenting configuration in your NixOS configs is great, up to a point. And that point is when you want to configure something that hasn’t been translated to a Nix configuration line yet.

Think of some hidden checkbox in that productivity suite that you use that isn’t recorded as a config file change anywhere. Think of some cloud-only app that saves host configuration using your hostname. Okay, perhaps those are contrived examples, but the fact is that not absolutely “everything” can be configured through NixOS.

And sometimes, that’s okay. Like for example, the desktop environment I use — KDE — has a bunch of options that I like to tweak for each system. But if I had to make a change in my configuration file each time I tweaked an option or messed with a checkbox, just to make sure the setting would persist if I ever reinstalled my system, I think I would go mad.

Of course, there are tools like rc2nix in the KDE instance that offers to convert

your current configuration into a Nix config. But in my usage, this hasn’t been

perfect, since the KDE suite of apps is inconsistent and store configuration files

in all sorts of places. (I mean, just look at Dolphin with its .dolphinrc.

rc2nix can’t capture that. Then you have to figure out where it is and what

config lines are pertinent to your specific host and then make a Nix config

for that in your config repository and make sure the symlink works and then make

sure new lines appended by Dolphin as you use it don’t get wiped out during

a rebuild and re-symlink and so on and so forth, and you can see why it quickly

becomes a massive headache.)

Like I mentioned with Dolphin, not all programs are friendly to being configured externally. Programs are meant to run anywhere, on most major operating systems, and on most major distributions if packaged for Linux. It’s very highly probable that the programs and tools you use do not know the existence of NixOS and are not written to be accommodating towards it.

And if a configuration change requires you to copy over or symlink a configuration file, any change you make within the program gets wiped out when NixOS rebuilds a generation and redos the configuration step, which is not a good user experience. You’re meant to configure “everything” (possible) through NixOS, but as we’ve established, you can’t configure “everything” through NixOS, so you end up with a bad time when the two configuration sources clash and overwrite each other.

Conclusion

So does that mean NixOS is bad and you shouldn’t use it? No. I still enjoyed my time using and learning NixOS. But I have a certain way of using my systems, and over time I’ve realized that my way of computing does not really match the declarative, immutable approach that NixOS takes.

Perhaps I’ll give NixOS another try once I have the time available to thoroughly learn Nix, and once the documentation for NixOS has matured to a point where it is easy to address some of the pain points I experienced above. But for now, I really just want to use my computer to do the things I want to do, and NixOS has become more of a hindrance with its cons than the benefits it provides through its features.

Footnotes

-

I say mostly here because of the con I’ll get to in a second. ↩

-

Which is totally valid, it is their right to do so! It does make it harder for users, so my point still stands. ↩

-

This is a really handy alias, and I’m not sure why it’s not the default. But you can configure it yourself if you want. ↩